Saturday, April 23, 2011

Why Doesn't God Do Something About Evil?

Many people who find the evidence for a Creator in natural theology compelling have a hard time believing that He could be good. He seems more like a disinterested deity who created and moved on without a backwards glance. As one atheist whose father was dying put it, "If this is the best God can do, he must've taken a half day on Friday."

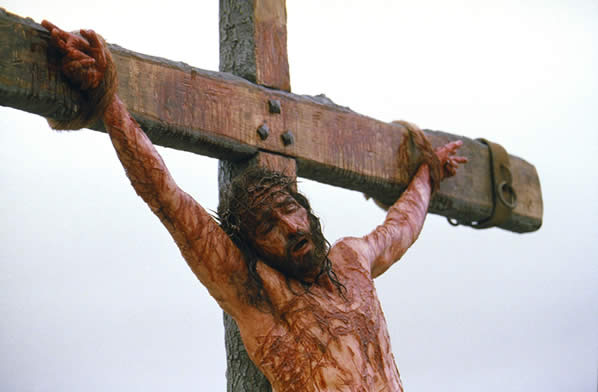

When he said that, it occurred to me that on a Friday afternoon, God defeated sin, suffering, and death forever on the cross. He finished His work of re-creation and opened up a way that will culminate in a new heaven and a new earth where our humanity is perfected and death and suffering is a thing of the past.

But He also used a powerful symbol to communicate His love for us even when we don't understand why there is so much wrong with the world. God came in human form and took upon Himself our sin and our pain. He died the most shameful and excruciating of deaths, between two criminals. He was present with the lowest of the low, promising Paradise to the repentant sinner (Luke 23:39-43).

From the very beginning, God planned to take responsibility for allowing evil in His creation, by sending His Son to die for us. Contrary to what Christopher Hitchens has said, this is not human sacrifice, something the Bible strictly forbids. It is self-sacrifice by God Himself, the ultimate expression of love and humility.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

The Problem of Evil and Suffering

|

| Masaccio's The Expulsion from Paradise |

I had a conversation with Lowell in the comments about a month ago where he asked me about a post that I wrote back in 2009: Venite Ad Me Omnes. It was about a crisis I went through eighteen years ago. I wrote it before I had any inkling that I would ever write apologetics, and reading it again through a skeptic's eyes, I wonder if it was irresponsibly written. I spelled out the gut-wrenching evil in great detail, but failed to talk in much detail about God's great goodness through it all. Just about everything I am today grew out of that experience.

When someone asked me a few days ago why I ended up engaging in dialogue with atheists, I explained that it was because I happened to have a conversation with an agnostic who told me about Atheist Central, and after checking it out I decided to comment. But I realized afterwards that the why goes back much further than that. It started when my five-month-old, Ingrid, had her first seizure the day after I had completed my requirements for graduation from Notre Dame Law School. Before May 12, 1993, Ingrid was developing normally--smiling and babbling to everyone, including stuffed animals and the baby in the mirror. Three months, three hospitals, and countless seizures later, she neither smiled nor cried and her right hand was fisted and unusable.

That's when I started asking the hard questions.

I've only spent a year-and-a-half thinking about the resurrection evidence, the fine-tuning argument, the cosmological argument, and the argument from moral law, but I spent a decade-and-a-half thinking about the problem of evil--called "the rock of atheism" by German playwright Georg Büchner. I don't claim to have all the answers, but I did gain some insights into the relationship between suffering, spiritual growth, and prayer over the years, and I will do a series of posts on that.

But I want to stress that the Bible is never overly philosophical about suffering. John 11:35 simply says, "Jesus wept" when He saw people grieving over the death of Lazarus. Jesus wept even though He knew that Lazarus would not remain dead. Evil is still evil and suffering still hurts even though God has reasons for allowing it. We are not to downplay the suffering of others by offering "helpful" platitudes. Instead, we are to "mourn with those who mourn" (Romans 12:15).

So I don't want to trivialize evil and suffering by a discussion of theodicy. C. S. Lewis said in The Problem of Pain that pain is God's "megaphone to rouse a deaf world." But he later wrote the following in A Grief Observed after his wife died:

Feeling, and feelings, and feelings. Let me try thinking instead. From the rational point of view, what new factor has H.'s death introduced into the problem of the universe? What grounds has it given me for doubting all that I believe? I knew already that these things, and worse, happened daily. I would have said that I had taken them into account. I had been warned--I had warned myself--not to reckon on worldly happiness. We were even promised sufferings. They were part of the program. We were even told, "Blessed are they that mourn," and I accepted it. I've got nothing that I hadn't bargained for. Of course it is different when the thing happens to oneself, not to others, and in reality, not in imagination.Pain is also a megaphone that drowns out reason, and it was not until we had settled into our new life with a severely disabled child that I was really able to reflect on the whys. But explanations are a pale substitute for what I did receive during those months in 1993: God's presence, joy, and peace like never before--the fulfillment of the promise of Jesus in Matthew 11:28: "Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)